A Nonprofit Leader in Need of Help

Angela* is the executive director of a small literacy nonprofit in the Pacific Northwest. Over the last few years, her organization has expanded significantly by partnering with local schools, launching a mobile library, and increasing program participation by nearly 60%. With so much demand for literacy programming, the future looks rosy, but behind the scenes, Angela is feeling overwhelmed. She has always played a hands-on role in fundraising—writing grants at night, personally calling donors, and organizing the annual benefit brunch with help from volunteers–but the work has begun to outstrip her capacity. Her staff includes a program manager, a part-time administrator, and two outreach coordinators, none of whom have experience with development. Donor communications are inconsistent, grant deadlines feel like a scramble, and her donor database is a spreadsheet.

Angela’s budget is tight, but her board is supportive; they’ve asked her to submit a proposal to build a development team, but she’s unsure about what positions would benefit the organization most. Should she hire a grant writer? A development director? Is there a way to build a team slowly, without overextending the budget? And how does she make sure that fundraising isn’t just one person’s job, but part of the organizational culture?

How to Start Building a Development Team

For leaders like Angela, knowing that fundraising needs to scale is just the first step. The next challenge is figuring out how to build a development team that matches the size, resources, and mission of your organization. CFA Head of Consulting and Principal Jake Muszynski offers a practical approach to building the right team for your organization: “Short of conducting a development assessment, the following steps can help increase capacity in a way that is discerning, sustainable, and mission-aligned: 1) assess your strengths and gaps; 2 ) clarify roles; 3) foster a culture of philanthropy; 4) invest in strategic hires and time-saving tools; and 5) measure your results thoughtfully.”

1. Assess Your Strengths and Gaps

The first step involves understanding what your nonprofit is doing to raise funds and determining what tactics are most effective. Jake encourages leaders to “strike a balance between leaning into areas of strength and shoring up deficits.”

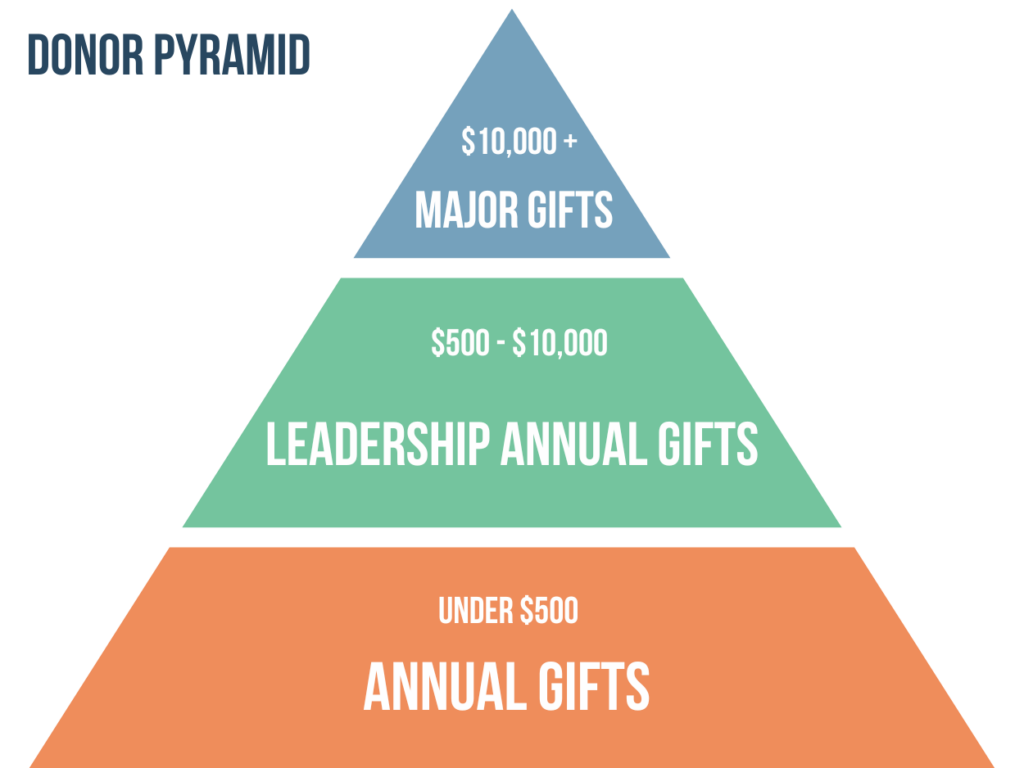

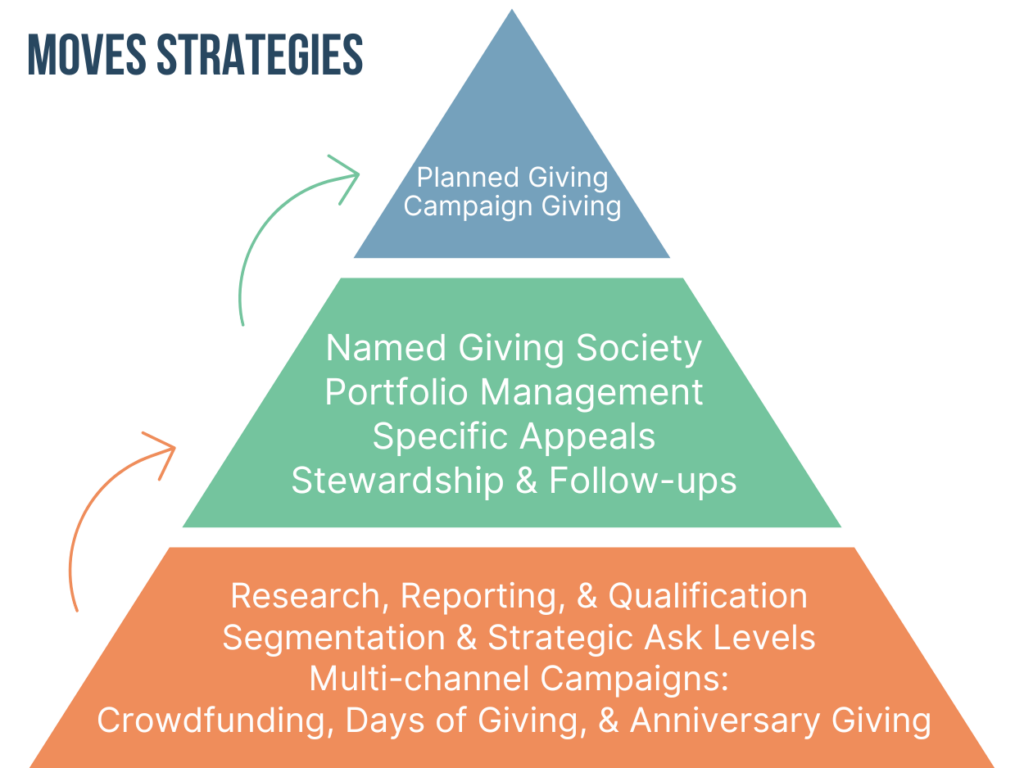

In Angela’s case, fundraising was almost entirely her responsibility. She delegated whenever possible, but her staff was at capacity, and fundraising tasks were slipping through the cracks. She sat down with her board chair and reviewed their current development practices and strategic plan. They talked about the typical roles on a development team (Development Director, Major Gifts Officer, Corporate Giving Manager, Grant Writer, Development Coordinator, Communications Specialist, Events Manager). Together, they explored how each role might enhance their fundraising operations.

Getting clarity on her organization’s strengths and gaps helped Angela see what work needed ownership, and where capacity was most urgently lacking. This reflection revealed that while grants were a major revenue source, she would need additional help to pursue grant funding in a more strategic, less frantic way. She also realized their individual giving program had stalled. She knew the lack of intentional and connected stewardship was costing them.

Angela decided the first hire didn’t need to be a high-level director, but a development coordinator—she posted an ad seeking a generalist who could manage data, send donor acknowledgements, support events, and serve as the primary contact for development. She designated the position as part-time with room to grow. At the same time, she hired a contract grant writer to stabilize their grant calendar and research new opportunities. She also asked her board if the organization could invest in a CRM database.

2. Clarify Roles

When working with clients to build out development teams, Jake emphasizes that each position should have a specific job description: “Clearly defined roles help everyone be more efficient.”

With a part-time development coordinator and a contract grant writer on board, Angela was able to clarify everyone’s role, including her own. The new development coordinator took over routine donor stewardship, event planning timelines, CRM data entry procedures, and general development inquiries. For the first time in years, Angela had the opportunity to regularly connect with key stakeholders and nurture those relationships. This clarity prevented the “everybody does everything” trap and ensured that no one was duplicating efforts or dropping tasks.

3. Foster a Culture of Philanthropy

Hiring a development coordinator didn’t mean that others stopped fundraising. Angela wanted to build a culture of philanthropy, where everyone—from board members to program staff—understood how their work supported fundraising. She introduced monthly “mission and money” updates in staff meetings, where she announced fundraising wins and team members shared stories and outcomes that could be used in appeals or newsletters. She also trained the board to make thank-you calls, helping them feel more connected to donors. The result? Fundraising started to feel like part of the organization’s DNA, not an avalanche of items on her personal to-do list.

4. Invest in Strategic Hires and Time-Saving Tools

Jake routinely cautions nonprofit leaders and their boards to be circumspect about low overhead: “Some organizations are very focused on having low ROI, but the fact is that it’s probably hindering their fundraising. When CFA is first getting to know an organization, no one ever tells us that they have all kinds of capacity. Nonprofits tend to err on the side of too little support, but a measured and strategic investment will enable most nonprofits to significantly increase their yield.”

The 2025 Philanthropy Pulse Report confirms that investing in team members works, finding that 7 out of 10 organizations that expanded their fundraising teams by 10% or more saw financial gains.

Angela’s organization purchased a relatively low-cost CRM in addition to hiring the development coordinator and contract grant writer. Before she began to invest in fundraising, Angela’s donor spreadsheet lived on her desktop, and appeal emails were sent through a personal Gmail account. Derrick, the new development coordinator, used the CRM to partially automate donor stewardship. He assembled for Angela a portfolio of their highest priority donors and devised a stewardship plan for Angela to follow, now that she had time to tend those relationships. In the end, these key investments saved time, reduced stress, improved professionalism, and increased the organization’s fundraising results.

5. Measure Results Thoughtfully

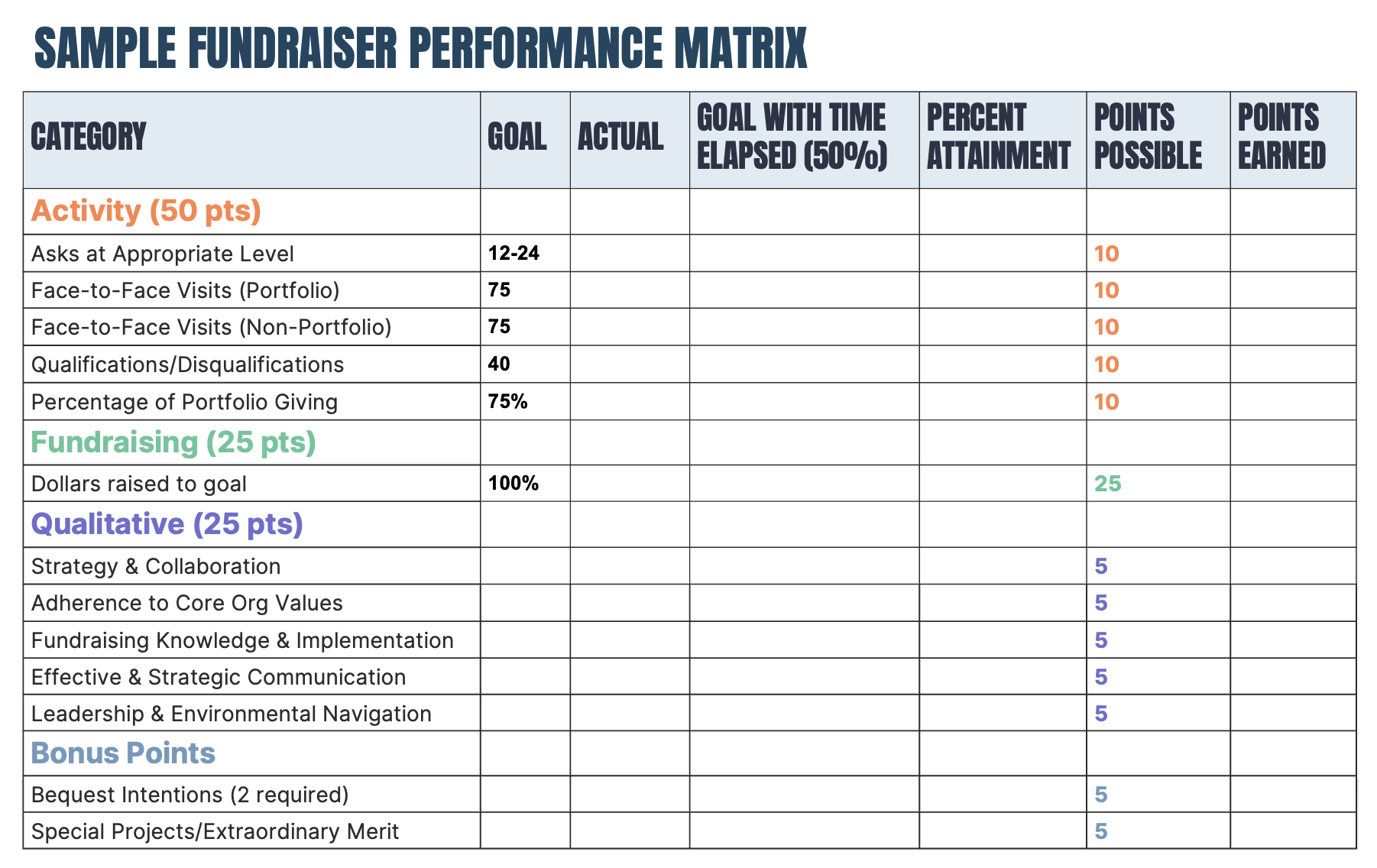

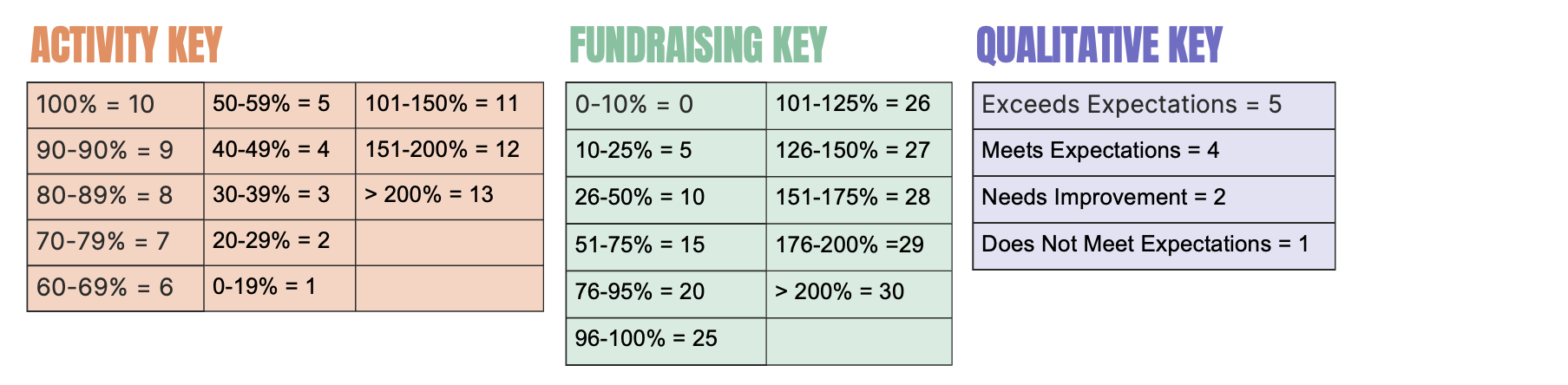

Measuring the return on investment is important, but Jake points out a few caveats:

“Organizations that rely upon philanthropy need to prioritize revenue generators when they hire, but it’s important to remember that if you hire a director of development or major gifts officer, it could take that person a year or more to pay for their own position or begin closing major gifts. This is the nature of relationship-based fundraising– it takes time to build trust and connection.”

Jake advises clients to use appropriate budgeting formulas to calculate ROI, but to do so with patience. Allowing time for fundraising personnel to build relationships is always less expensive than starting over with new hires.

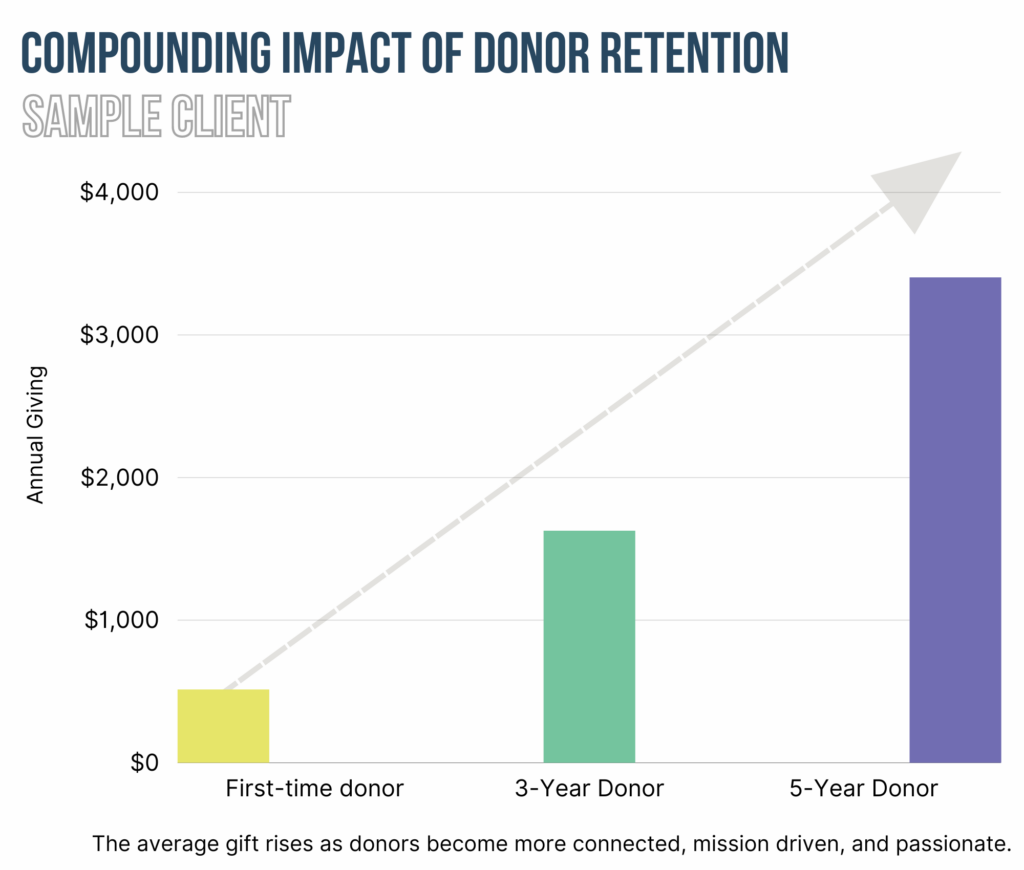

Angela’s budget didn’t have much room for error, so she opted to step into the role of “revenue generator” herself. After all, she was already connected to the most engaged donors, but she hadn’t had the time to steward them mindfully. Angela wanted to pilot intentional stewardship in her organization to see what it would look like. Her long-term plan was to gradually increase the responsibilities of the development coordinator over time, eventually transitioning the position to full-time and possibly expanding it to oversee annual appeals as well. In the meantime, she and Derrick worked together to track not just dollars raised, but other gains, too: donor retention and upgrade rates, grant application win/loss ratios, email open and click rates, and time saved on administrative tasks.

Over Time, A Bright New Future Emerges

Eight months on, Angela had a clearer picture of her organization’s needs. With stronger systems, a more stable fundraising rhythm, and increased revenue, she converted the development coordinator position, Derrick’s job, into a full-time role. He had trained as a part-time employee, gradually gaining more expertise in the organization, so when he started full-time, he hit the ground running. By starting small and scaling intentionally, Angela avoided overhiring and instead built a structure that could last.

Jake’s final summation: “Building a development team is not about copying another nonprofit’s org chart. It’s about starting where you are, identifying your most pressing gaps, and growing from a place of clarity and mission alignment.”

Angela didn’t fix everything overnight—but with the right hires, better tools, and a culture that shared responsibility for fundraising, she stopped feeling like she had to do it all alone. And that, more than any one role, tool, or tactic, is the foundation of a strong development team.

Partner with Us

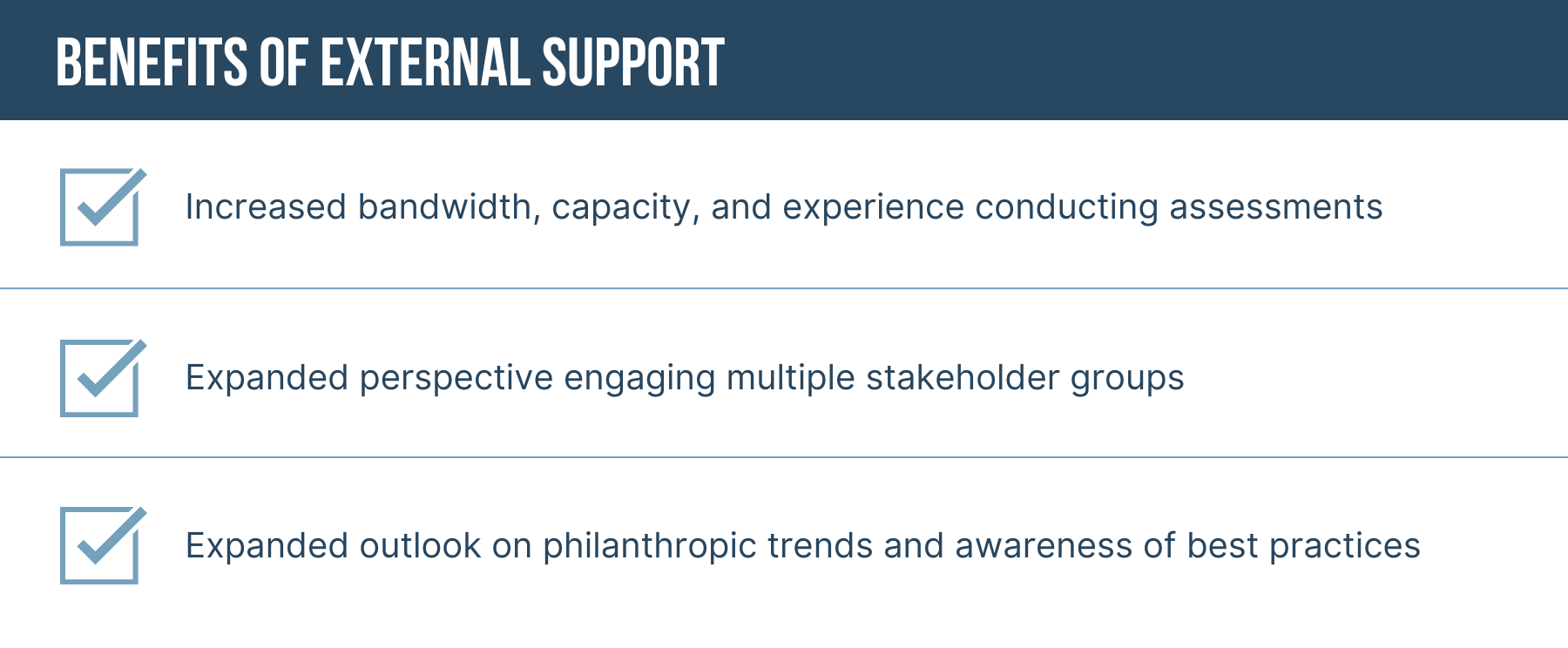

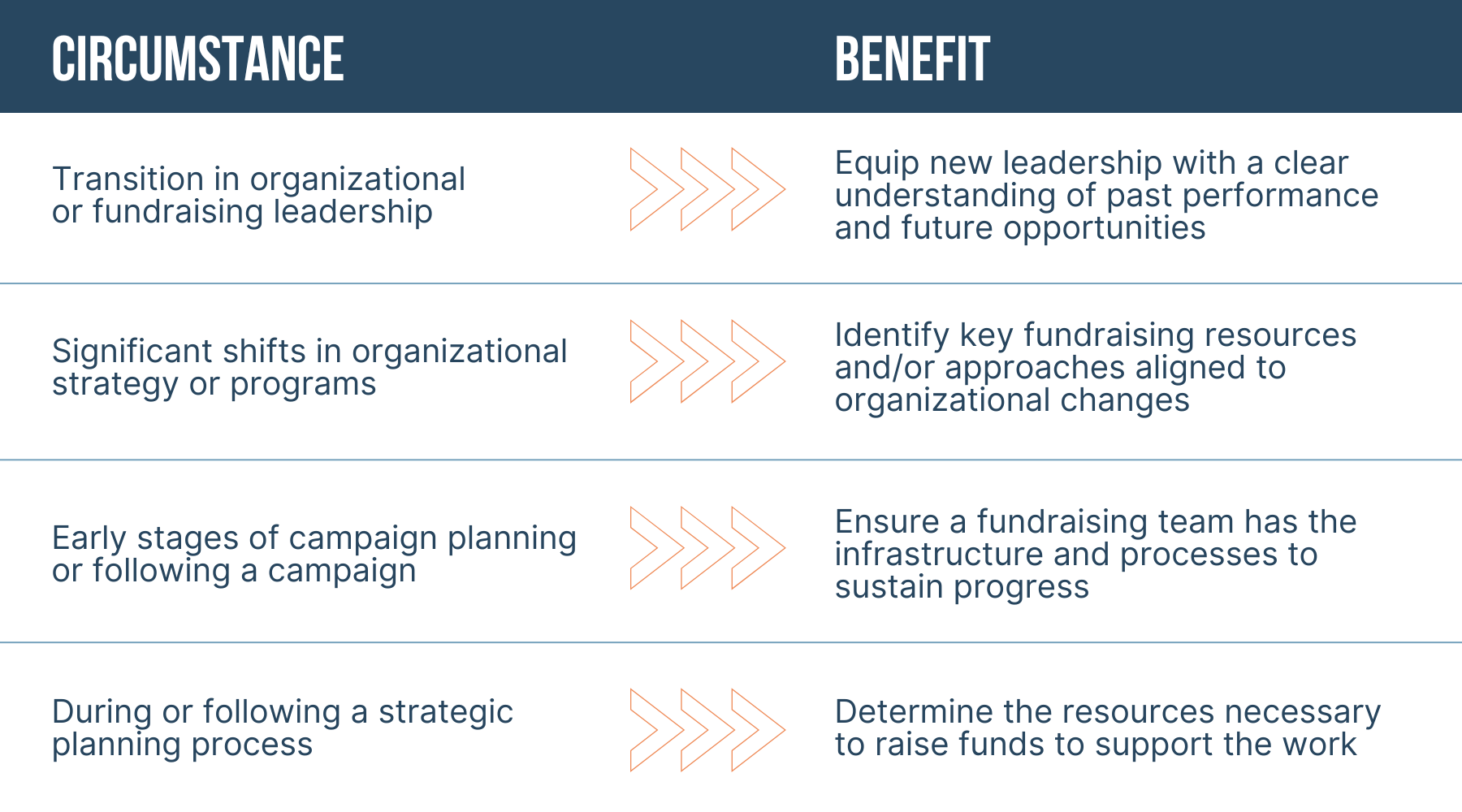

Is your team stressed, working at full capacity, and barely reaching goals? Do you sometimes worry about staff burnout? Are you unsure about how to expand your development team? CFA can help right-size your team with a development assessment, a comprehensive analysis of fundraising operations that enables us to pinpoint the new roles that will optimize your team’s capacity and achieve the results you need. Contact CFA today.

*Disclaimer: Client confidentiality is paramount in our work with each and every organization. The story in this article is fiction, based on real situations drawn from CFA’s broad experience serving nonprofit organizations.

Leslie Cronin, Senior Manager of Strategic Communications

Leslie Cronin comes to Creative Fundraising Advisors with broad experience in education and nonprofits. Early in her career, she taught English, composition, and creative writing at selective independent schools, colleges, and universities. In 2005, she became Senior Development Writer at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, overseeing all aspects of communication coming out of the museum’s development department including exhibition descriptions, grant applications, correspondence with major donors, acknowledgements, and event invitations.

Leslie later brought her experience in education and fundraising to a new role, serving first as board member and then vice president of the board of an independent school in Houston, Texas. During her tenure, she was instrumental in the formulation of the school’s 20-year plan, including its successful accreditation as an International Baccalaureate institution. She worked closely with a wide variety of consultants on urban planning, architecture, and a fundraising feasibility study. Her insight into the client experience helps her every day in her work for CFA.

As Senior Manager of Strategic Communications, Leslie helps CFA’s clients shape their campaigns for maximum impact and results by leading case development workshops, writing compelling case summaries, and crafting powerfully persuasive campaign collateral. Additionally, Leslie manages CFA’s brand voice by developing content for the firm’s resource library and overseeing the editorial calendar.

Leslie believes nonprofits have the power to change the world. In crafting cases for support, she writes as a committed advocate for each client and their goals. Leslie holds two Masters degrees, one an MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, the other an MA in English Literature from Temple University. She is mother to two grown children, a voracious reader, and an amateur equestrian. She lives on Cape Cod with her husband, author Justin Cronin, and their rescue dog, Lonesome Dove.